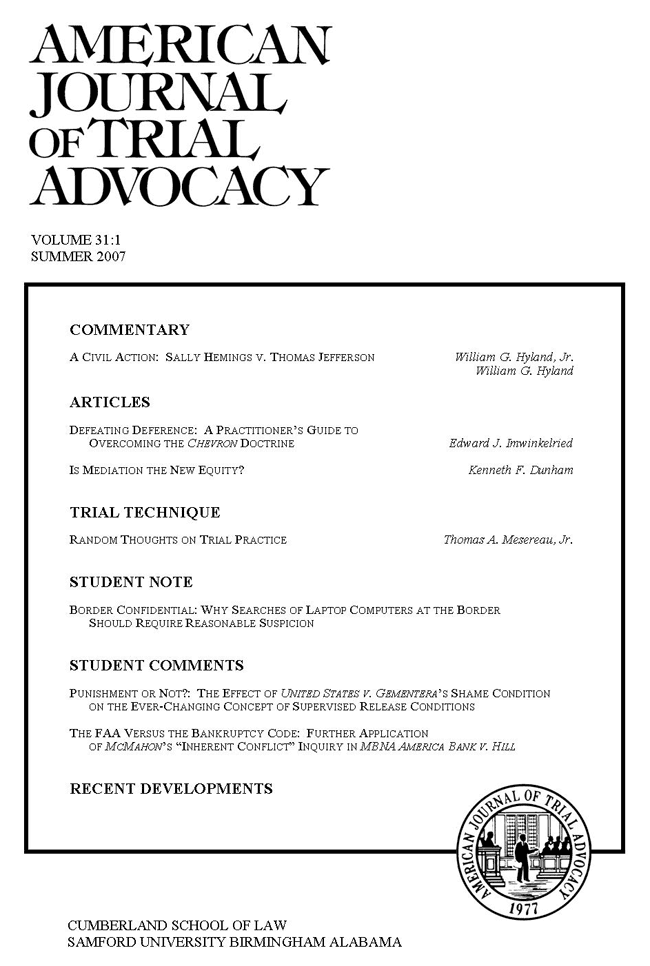

Speech to Cumberland School of Law, Spring, 2007

by Thomas A Mesereau Jr.

Abstract

In the Spring of 2007, Thomas Mesereau visited Cumberland School of Law and discussed unorthodox trial techniques that have helped him prevail through almost insurmountable circumstances. Mr. Mesereau discusses the unorthodox techniques against the backdrop of classical trial technique methods. The speech centers on jury selection, the opening statement, witness examination, and dealing with the media in high-profile cases.

Introduction

First of all, thank you so much for inviting me to be your speaker today. I am very appreciative, honored and excited about it. I am here to help you any way I can within the short time I am available.

What I plan to do is talk to you about various things that I consider important to all of us in the trial of cases. I will accept questions from anyone, either during my talk or afterwards. I am very flexible and here to help.

What a beautiful campus! Before arriving, I took a little drive through and thought to myself, “What a beautiful place to go to law school.”

I am informed that Cumberland emphasizes the development of trial practice skills. It is very satisfying for me to hear this. Too many law schools neglect the real fundamentals of what it takes to be a skilled trial attorney. At most of these excellent institutions, trial practice is simply one course among many and does not receive the emphasis it merits.

At various moments, trial lawyers hold peoples lives in their hands, hold peoples finances in their hands, and have a great influence over the client’s future life, reputation and welfare. To send lawyers out to try cases who really do not know what they are doing is a great shortcoming in our profession. I am so happy that your law school is trying to do something about this problem.

I have some views on trying cases that are not very conventional or orthodox. In fact, they deviate quite a bit from what we are taught in law school about how to try a case. I will articulate and explain my thoughts in this regard, but I am not asking anyone to robotically copy what I describe. I only wish to provide some food for your thoughts about the courtroom as you learn who you are and how you fit in as a trial lawyer.

I. Intellect Versus Intuition

To me, the most important thing an aspiring trial lawyer can do is put in the time and effort to learn who you are and how you relate to the particular chemistry of a courtroom. Every time you try a case, you are engaged in a unique process and experiment in the lives of people. You are not just dealing with their intellect; you are trying to reach their hearts, souls and spirits. You need to do your best to learn about the hopes, fears, dreams and aspirations of ordinary human beings who are doing their best to be responsible citizens, serve as jurors and to lead a good life. You need to know what excites them and what disappoints them. Insight into human nature is extremely important to the trial lawyer.

We do not always learn such things in law school. For the aspiring trial lawyer, too much of what we are taught in law school occurs on a highly intellectual level as opposed to a human level. We are taught to be intellectually contentious and to fiercely argue different positions on different subjects. Of course, all of this is very important to the developing lawyer. But it is not enough if you are going to master the courtroom.

The best trial lawyers know themselves fairly well and have a keen insight into others. And when I say “others,” I mean all kinds of human beings. When you address a jury, you are trying to reach out to a cross-section of your community and not of your law school.

For example, when I see a corporation or corporate executive in trouble, I often marvel at the lawyers they choose. Like most people in society who are challenged, they will pick as their agent or representative someone they feel comfortable with. What they fail to realize is that the more important question is who the jury will relate to. There is often a huge difference, a sometimes fatal difference.

Some of the greatest trial lawyers are people who either did not do well in law school or were erratic in their studies. What I have observed about these lawyers is that they seem to like human beings. They like to talk to people, study them, empathize with them. And in the courtroom, these lawyers feel as much as they think. Intuition can be so important for a trial lawyer.

Much of the time, my job is to humanize someone who has been demonized for months by the prosecution. I have to do this in front of twelve strangers whom I know little about. The stakes could not be higher because the other side is trying to destroy a life you are trying to save. To reach the hearts and minds of these twelve unknown citizens requires much that cannot be learned in books or mock trials. You have to live a good portion of your life in the courtroom and do everything you can to love and relate to people.

II. Traditional Teaching

Of course, I realize you are being taught the classic fundamentals of trial practice. This is very important. You have to not only master these fundamentals, but learn the reasoning and philosophy behind them. For example, when you are taught not to ask a “how” or “why” question on cross-examination, your professors are not just telling you this to hear themselves talk. There is a very important reason behind these fundamentals. But I have to be honest with you; I break this rule all the time. I believe all good trial lawyers have to.

When your professor tells you to tread lightly in your opening statement lest you promise too much, there is a valid reason for this principle. The reason is that your credibility in front of that jury is very important. Credibility can be everything in a trial. A lawyer who has credibility has a tremendous advantage over one who does not.

Nevertheless, I sometimes give opening statements that have people wondering what I was taught and where I am coming from! People v. Jackson was an example of this. I will discuss this further in my talk today.

You are also taught to keep witnesses under control and with a tight rein. Law students are often taught to prepare a witness to simply answer the question and not deviate or go off on tangents. The theory is that the more a witness says and reveals, the more ammunition you provide the other side for cross-examination. But I break this rule often, and I broke it repeatedly in the Jackson case.

III. Flexibility and Spontaneity

We are taught so many things about how to be careful in a courtroom and how to not go too far over the edge lest we embarrass ourselves. But sometimes you need to take risks to have a chance at winning. In my opinion, the best trial lawyers periodically take risks and sometimes get burned in the process.

The bottom line is that you are mastering and understanding a human process that is unique to each case. When you are in a courtroom trying a case there is never going to be another moment quite like that one. The particular interaction and chemistry between the judge, witnesses, lawyers and evidence will never be duplicated. This chemistry will evolve and change throughout the trial and is very much affected by what you as the trial lawyer do. Reaction and spontaneous decision making are critical, and the proper reaction will often require that you scuttle ideas and strategies that you had spent considerable time preparing. When confronted with the unexpected in the courtroom, flexibility is critical. The flexible lawyer is the better one.

For example, in the Jackson case I prepared and reviewed twenty binders of material for the critical cross-examination of a major prosecution witness. During my cross-examination, I did not use a single binder! The witness came across very differently than anticipated. Instead of the vigorous cross-examination intended, I delicately and gently conversed with this witness in a non-hostile manner. She became my witness. My decision how to cross-examine this witness happened quickly and spontaneously. I had to seize the moment.

IV. Public Opinion

You start any trial with a certain feeling about the emotional environment. This is especially true in a high-profile case. The media will create an emotional landscape that the trial lawyer must understand but not overreact to. In the Michael Jackson case, the general consensus was that the case was unwinnable. However, criminal defense lawyers can never overreact to any media created context. I have great faith in juries and know that they often disappoint the media by doing their job. For example, the media thought O.J. Simpson would be convicted, but he was acquitted. They thought Robert Blake would be convicted, but he was acquitted. Quite clearly, they thought Michael Jackson would be convicted, but he was acquitted. Finally, most media representatives I know thought Scott Peterson would either be acquitted or experience a hung jury. He was convicted and received the death penalty.

Just because you see and experience this groundswell of public belief and negative media conclusions does not mean what they predict will actually happen. American juries tend to be very independent and try to follow the law as best they can. They know what they are being asked to do to a person, as well as the people in the life of that person. Lots of lives are in the juries’ hands. For this reason, I think American juries tend to be at their most intuitive, most instinctive, most intellectual and most intelligent level when they are deciding a criminal case. I think juries tend to get more intensely involved in criminal rather than most civil cases.

I have spoken to jurors in criminal cases who told me that they had trouble sleeping as they heard and decided the evidence. I have not had a civil jury relate such a problem to me.

V. Opening Statement

Let us return to my thoughts on opening statement. Opening statement must relate to the emotional circumstances surrounding this particular case. It is a conversation, not a speech. You have to orient your opening statement to the emotional needs of the moment.

When I walked into the courtroom in the trial of Michael Jackson, I was acutely sensitive to the media groundswell about prior allegations of molestation, multi-million dollar settlements, discourse about how weird Michael Jackson allegedly was, claims that Michael Jackson could not relate to any normal person, and all the other circulating rumors. I considered all of this to be highly prejudicial and disturbing. People with a vested interest in a conviction were trying to spin a verdict before the trial even began. I had to account for all of this in my opening statement.

My opening statement in the Jackson case generated a lot of criticism from the television pundits who were examining everything I did through the lens of trial practice fundamentals. They were gauging what I did by comparing my methods to the principles you are learning in your trial practice class. For example, in a criminal case the prosecution must prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. The defense has no burden to prove anything. Despite this theoretical advantage, I made promises and assumed various burdens of proof in my opening statement in Jackson.

I said I would prove that Michael Jackson was innocent and asked the jury to hold me to my contract with them. I invited the jury to watch me prove what I promised. I did this for a particular reason, which had more to do with the environment surrounding this trial and the chemistry of this courtroom than anything else. I felt that if I just “tiptoed” through the evidence, as I had been taught in law school, I would never catch up. The emotions of this courtroom had to be immediately seized and, as much as possible, never relinquished. I could not appear “scared of my shadow” or afraid to say something that might not be proven later on.

This strategy had more to do with human intuition and emotion than anything I was taught. Every trial has unexpected developments and surprises that can knock you off kilter from a strategic and tactical standpoint. While what you say in opening statement must have a good faith basis, and while you certainly want to demonstrate what you claim you will accomplish, you know that you will have to “shift gears” during the trial. In the Jackson case, I was willing to risk not proving everything I said I would prove as the trial took its inevitable unpredicted course. However, I believed that if I did not seize the emotion in that courtroom at the outset, I was in trouble.

VI. Trial Theme

Now I think most of you have been told that jurors are instructed not to form conclusions until all of the evidence is in. They are instructed by the trial judge to not form such conclusions on a daily basis. For this reason, many law students are taught not to emphasize their arguments and points until closing argument. I think you probably have been told this because that is what most people are taught and that is what most people do.

In the Jackson case, my reaction to this principle was baloney! People make up their minds all the time and quickly. Once they form their conclusions, many people are stubborn and do not want to change their views unless you hit them over the head with a mallet. I had to grab the momentum immediately, take risks and look into people’s hearts and say the things I thought would move them. Remember, there was more media covering this case than the criminal trials of O.J. Simpson and Scott Peterson combined. And ninety-nine percent of what the press reported was negative. This feeding frenzy was disturbing to me and still is.

The dictates of big business were all over the Jackson case. Hundreds of millions of dollars would have been made from a conviction in news stories, documentaries, ratings, and television revenue. Hundreds of cable stations were vying for the latest inside information in the case. All were looking over each others’ shoulder and trying to outmaneuver each other with the latest scoop. A conviction meant endless stories from the jail about suicide watches, what he was reading, what he was eating, and every other detail of his existence. If sentenced to prison, the sentencing hearing would have been the biggest in world history. A not-guilty verdict would be a major disappointment to major business interests around the world.

This made it even more imperative that I aggressively and powerfully grab the momentum early in this case. I also had to combat the realization that the case was being misreported everywhere in an effort to spin a conviction. There were days when I came out of the courthouse, traveled to my condo and went to work. During a break, I would channel surf the television to view the coverage.

I would often wonder what trial they were watching! Clearly, winning this case required unconventional, unorthodox, creative and risky strategies and tactics. Of course, the pundits were wondering what was wrong with me. Following my opening statement, television commentators did not understand why I would assume burdens that legally were not required. Of course, the elements of a trial are not simply legal. They are also emotional and human. Theory alone does not give you the tools to win a high-profile trial.

The concept of reasonable doubt is a tricky one. Of importance to me was not what it meant to law students or law professors, but what it meant to the human beings on the jury. Here is what I concluded:

“The heck with reasonable doubt, I won’t raise it until my closing argument. These good, honest, hard-working people want to know the truth and they think the lawyers know what happened. I have to approach them as the one most willing to present the truth and not as someone hiding behind legal concepts or burdens. Otherwise, we’re cooked!”

Sometimes lawyers know the truth and sometimes they do not. But jurors think we do. They want to know the truth and the lawyer who presents herself to them as representing the truth–and not being afraid of it–will often have a better chance of winning. In Michael Jackson, had I talked about burdens of proof, presumptions of innocence and reasonable doubt in my opening statement, I believe the jury would have concluded that my client was guilty and that I was trying to deflect them from that reality. It would have looked like I was hiding behind technicalities. When you discuss these principles with your fellow law students or the wonderful professors at this great law school, you are not trying to persuade a jury of hard-working people who are forced to accept a pittance for their jury service.

In Jackson, I had to “come right out of the box” and let them know that, no matter what they had heard about the case, I was the bearer of truth. I challenged them to just watch me “prove his innocence.” And that is exactly what we did.

I was very critical of the legal pundits who commented on the trial. To me, most of them knew nothing and did nothing. Why were they on these daily shows being paid nothing to passionately criticize what happened in a courtroom that most of them had never seen? Why would somebody in a New York office who did not know the evidence or the witnesses get so passionate in front of a camera? It was absurd.

I remember Johnnie Cochran’s comment after O.J. Simpson’s acquittal about the legal pundits who thoroughly misjudged his capabilities and performance. He said that he was trying the case in the courtroom while they were trying it outside. There is a big difference.

In a high-profile case you have to truly tune out the pundits and not care about them at all. If you worry about them too much, you can easily forget who your audience is. The only real people you care about are the judge and twelve jurors.

VII. Approaching the Witnesses

A. The Mother

I mentioned earlier that I often deviated from fundamental principles of cross-examination in the Michael Jackson case. Of course, I was taught not to ask a “how” or “why” question on cross-examination for obvious reasons. Such a question invites the witness to ramble on with self-serving statements in an uncontrolled way. We are taught never to allow a witness to “run at the mouth.” We are asked to assume that, if given the opportunity, a witness will have been prepared by a lawyer to run in all sorts of directions that are damaging.

I want to comment further on this principle, but before I do I need to emphasize something. I am not telling you to copy any of the things I am articulating today. I am only asking you to think about my comments as you develop your skills and approaches.

In the Jackson case, I knew that the key accusers for the prosecution had been prepped by one of the best civil lawyers in Los Angeles as well as the district attorney. I assumed these witnesses were prepared for me to make a mistake by asking a “how” or “why” question on cross-examination. Nevertheless, I sometimes did so. Why?

In deciding what you wish to accomplish in a witness examination, you are always weighing costs and benefits. Everything you do has a benefit and a drawback associated with it. If your goal is to get the witnesses to reveal their flawed character, inherent dishonesty or rehearsed testimony, it is harder to accomplish this if you ask questions that require tight control. It may be that asking a “how” or “why” question is worth the candle no matter what the witness says. In fact, if you think a witness has blindly rehearsed a response that the jury will see through, you may want to encourage that response. The price you have learned about in your trial practice class may be worth paying in order to reap a greater benefit in the trial.

In the Jackson case, one of my principle themes was that the mother of the accuser was a con artist. I had a lot of evidence to support this. I told the jury I would prove that the mother had schooled her children to target celebrities for money. I argued that this family knew a criminal conviction would automatically lead to millions of dollars in damages in a parallel civil proceeding. You simply take the judgment of criminal conviction and file it in civil court. All that is left is how much money will be awarded in damages.

I concluded that the mother was shrewd, conniving and dishonest. However, I did not think she was very bright. No matter how prepared she was, I did not think she could withstand days of cross-examination on the witness stand. I believed that the more she talked, and the more I encouraged her to talk, the more canned, rehearsed and fake her testimony would be. I proceeded accordingly.

The prosecutor put her on the stand for direct examination. She would not stop talking in response to his basic questions. I refused to object and let her simply talk on interminably. Fellow lawyers were shocked at my approach. Why?

Quite reasonably, they thought I would want to control this witness and prevent her from making randomly damaging remarks. I wanted her to make them. I felt that the more she talked the more fake she would appear! I refused to object.

I had a co-counsel who is a very skilled and accomplished trial lawyer. When I refused to object to this witness’s rambling responses, he looked at me like I was crazy. I told him to calm down and that I knew what I was doing. I let her give speeches about how Neverland was a haven for booze, pornography and child molestation. I let her go on and on and on. It was a debacle for the prosecution.

The prosecutor kept looking at me and hoping I would object. I just sat there. Suddenly he started objecting to his own witness. Every time he asked a question, this witness rambled. He would then object that his own witness’s responses were “non-responsive” and “move to strike.” “Stricken” the judge would say. And I would just sit there letting her talk a blue streak. The prosecutor’s objections to his own witness made her appear even worse!

I had often objected to the testimony of previous witnesses and my sudden change in approach was even more apparent to the jury because of this. They clearly noticed the different dynamic with this witness. Following the verdicts, a couple of jurors told me this mother was a total disaster for the prosecution.

Suppose I had followed conventional practice and cut off her rambling responses for the sake of control. Would I have been better off? Actually, I would have been better off in the trial transcript and record. I would have looked more confident, educated and professional. But the trial record does not capture the emotions and persuasive nuances of the trial. Had I followed the conventional approach, you students would have read the transcript and concluded I was a smart lawyer who had studied trial practice in law school. You would have probably complimented me on my ability to control the witness. But one of the key witnesses to our victory would have been allowed to escape in the process. Effective trial lawyers sometimes do not appear well on transcript. Conversely, ineffective ones often make perfect transcripts.

B. The Alleged Victim

There is a law professor in Los Angeles who is a good friend of mine. Her name is Laurie Levenson and she teaches at Loyola Law School. She is a frequent television commentator on legal issues and a former United States attorney. I am sure some of you have seen her.

Laurie is very highly respected in my city and I was recently privileged to address her criminal procedure class. When she introduced me, she commented on my cross-examination of the thirteen-year-old accuser in the Jackson case. She commented on my cross-examination question that she felt had won the case for the defense. That question was “why?”

I had studied this child accuser as he responded to the district attorney’s questions in direct examination. I thought I had a pretty good feel for this witness. To me, he was a thirteen-year-old boy “going on thirty.” In my opinion, this witness was clever, dishonest, deceitful, cool and with an obvious agenda. He had taken acting lessons and appeared to like being in the spotlight. I sensed this the moment he appeared in the witness box.

I believed that this child accuser was angry at Michael Jackson, but not because he had ever been molested. I believed he and his family had hustled celebrities like Chris Tucker, George Lopez and others and that his family thought they had “hit Lotto” when they met Michael Jackson. This was a low-income family whom Michael let move to Neverland at various periods. Because the thirteen-year-old boy suffered from cancer, Michael took them on trips, had a blood-drive and did all sorts of wonderful things for the family.

The accuser’s brother was one year older and wanted to be a producer. Michael helped him produce a video at Neverland and was constantly doing nice things to assist this family. But then, Michael got sick of them. He got tired of them leaning on him and began to pull away. The children started calling Michael “daddy.” The mother started calling him “daddy.” I believed that these false molestation claims began when the family realized they were on the way out.

As clever as this thirteen-year-old boy was, he was not smart enough. He had lied previously in a civil deposition where his mother made false claims that she was molested by security guards at JC Penny stores. In my cross-examination, I spent a lot of time trying to reveal to the jury who this thirteen-year-old really was. I could not have done so if I confined him to “yes” or “no” answers. You only learn who people really are when they talk and reveal themselves. I believed self-revelation was worth the price of relinquishing witness control.

I warmed up this witness for the key question. My questions went something like this:

“You and your family wanted to stay at Neverland, correct?”

“You wanted to take trips with Michael Jackson and did so, right?”

“You went on amusement rides with Michael Jackson, didn’t you?”

“Michael Jackson introduced you to people you could only dream about actually meeting, right?”

“And at some point you became very angry at Michael Jackson, didn’t you?”

“Why?”

This child accuser began to ramble about how Michael had abandoned him and his family. He never mentioned anything about child molestation!

Of course, I am not saying that any of you should copy this approach. Just think about it.

C. An Uncooperative Witness

We are taught the value of witness control on direct examination. Of course, witness control can be important. A witness who goes on a tangent can provide good ammunition for a skilled cross-examiner. However, you must ask yourself what you are trying to accomplish.

Do you learn much about a person if they give short, clear, crisp answers? I do not think so. If you want the jury to see and feel the character, personality and values of your witness, you may want them time to talk in an uncontrolled fashion. Of course, you run the risk I have just described in cross-examination. But what if you think the risk is worth having the jury look into the motives and character of your witness or client? Maybe you have achieved a greater good in this unique arena called the courtroom.

Yes, there are some witnesses I want to confine but there are other witnesses I want to speak from the heart. It is a judgment call for the trial lawyer. This is an art, not a science. It sometimes has more to do with what you believe is necessary on a human, emotional level than what looks theoretically desirable. Sometimes your human soul gives you messages that your legally trained intellect rebels against.

I remember Johnnie Cochran’s words in his first book, where he said that he had to reach the hearts as well as the minds of his jury in the closing argument of the O.J. Simpson trial (Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. with Tim Rutten, 1 Journey To Justice 336 – 1996) I am not aware of any course in any law school that tells you how to peer into the hearts and souls of hard-working people who sit on juries. You learn it by caring about people, being curious about people, and learning how to talk to anyone, not just your colleagues. You must understand people when they sit in your office as you find out who they are and what actually happened. If you are inspired and motivated, you will go to their homes, their offices or whatever part of town they are from and learn who they are. This will help you humanize the people you represent who are being attacked. You also become a better human being in the process.

As I alluded to previously, Michael Jackson was thoroughly demonized in the world press before and during his trial. Many called him the best known celebrity in the world, even better known than Elvis Presley. The media ganged up on him and were salivating over his dramatic rise and fall. This affected their coverage and reporting of what witnesses meant to the trial.

For example, I called Jay Leno as a witness in my case. He did not want to testify. His lawyer made this very clear to me on the telephone. As lawyers always do when they want to discourage someone from calling their clients as witnesses, he suggested that I would not like what his client had to say. He suggested to me that his client was not going to remember what the accuser or his mother had said to Mr. Leno in a phone conversation. To the attorney’s great surprise, I informed him that I had a tape recording of Jay Leno’s conversation with the Santa Barbara sheriffs. Mr. Leno had been secretly recorded telling the sheriff’s investigator about his conversation with the accuser. I told Jay Leno’s lawyer that it would be very embarrassing for him to have me impeach his client with his own recorded statements. I then offered to forward a copy of this tape to this attorney prior to our next conversation. I did so.

Jay Leno, whom I do not believe cared for Michael Jackson, was honest in his phone conversation with the sheriffs. He said the accuser had repeatedly tried to reach him and that he had had at least one conversation with this thirteen-year-old boy. Mr. Leno made clear that he supported the prosecution but had to be honest in his appraisal of the young man. He was very uncomfortable with the conversation and felt that this thirteen-year-old boy seemed overly rehearsed and scripted. Jay Leno said he had talked to many thirteen-year-olds before, but this one was very different. He claimed a woman was in the background who appeared to be encouraging this boy in what to say. He thought they wanted money even though they did not actually ask for it. After the phone conversation, Jay Leno told his manager not to put anymore of their calls through.

Jay Leno told the police he thought this young man and the woman in the background were “looking for a mark.” Of course, I called him as a witness and he was devastating to the prosecution. His testimony fit comfortably with my opening statement and case theory.

When I came home that day, I made the mistake of turning on the television to see media reports of Jay Leno’s testimony. The reports were typically like this: “Leno blows up on defense, says accuser did not ask for money!” This is why you need a thick-skin to try a high-profile case.

VIII. Reasonable Doubt

As I suggested earlier, I did not emphasize reasonable doubt in the Michael Jackson case until my closing argument. Of course, I realize that 99.9% of my colleagues do not agree with this approach. They usually start conditioning jurors during the voir dire to understand the concept of reasonable doubt and its historical importance. They will use this concept to explain why our justice system is the best in the world and sprinkle this term throughout their questioning in the trial.

In most of my cases I never mention burden of proof, presumption of innocence or reasonable doubt until the very end. I want the jury to know that I am the bearer of truth from the outset. When I finally mentioned reasonable doubt in the Jackson case, I said words to this effect:

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, we have repeatedly proven that Michael Jackson is innocent of these horrible charges. We have proven this over and over again. You have never heard me mention the words “reasonable doubt.” I did not have to. But now, our trial judge has instructed you that you must follow the law of reasonable doubt. Because of this obligation on your part, I must now explain this to you.

I never looked like I was hiding behind a technicality. I was simply explaining the law that the trial judge said must be followed. I went through the evidence in detail to explain how any honest, law-abiding person had to conclude that the prosecution’s case was riddled with problems and not proven.

IX. Jury Selection

A. Intuition

I began this talk by discussing human nature and why we trial lawyers must have a good feel for and understanding of people. In this regard, I would like to discuss jury selection in the Michael Jackson case. In this case, I had a jury consultant. This was only the second time I had ever used one. The first instance was when I was defending actor Robert Blake against murder charges. My other clients were never wealthy enough to afford this option.

Jury consultants are often psychologists or social scientists who have a knowledge of statistics and analytical methods. This allows them to investigate attitudes and values in the community from which a jury will be picked. For example, they will conduct phone surveys to determine what people have heard about a case and what has influenced them. They will take this data and correlate it to income, race, religion, politics, location, occupation, etc. They will develop a composite profile of an ideal prosecution juror and an ideal defense juror. They will identify the primary ideas and influences for each category in order of importance.

For example, in the Jackson case, Michael had done a tremendous amount of charity work for children, disabled people and others. This was the primary factor that influenced pro-defense jurors according to our consultant. The fact that Mr. Jackson had paid millions of dollars in civil settlements to litigants who claimed they were molested was what primarily influenced pro-prosecution jurors to believe he was guilty.

All of this data was valuable to me. I had never tried a case in Santa Barbara County, California before the Jackson trial. This county is north of Los Angeles County where I primarily practice.

In choosing my jury, I have to admit that I discarded most of the jury research data referenced above. There is something deeper about human nature than survey data. In my opinion, any lawyer that routinely or mechanically applies this data in jury selection is doing a disservice to his or her client. The data is instructive and comforting to have, particularly if you are trying a case in a different area than you are used to. It may even tip the balance in the decision to include or exclude a particular juror. Nevertheless, your instincts and intuitions are far more important. And, as I said previously, intuitions spring from an interest in people, a love for people, and a feel and concern for human beings.

Let me give you an example of what I did. We all know that child molestation allegations are ugly and disquieting. For this and other reasons, the jury consulting data suggested that I not choose women with children as jurors. The idea was that these allegations would disturb mothers more than anyone else and strike at their motherly instincts to protect children from predators. This conclusion was reasonable and rational.

Nevertheless, I wanted women and, in particular mothers, on my jury. The Jackson jury had eight women and four men. Why?

Of course, I do not have time to tell you much about the specifics of the people I included or excluded, but I will give you a certain generality to think about. I was representing someone who was being vilified and demonized as a weird, male predator. In the process of monsterizing Michael Jackson, the prosecutors randomly attached his sexuality. They did this through the types of questions they asked throughout the trial. They would make references and ask questions suggesting that he was asexual, homosexual, effeminate, slept with “little boys” and other similar things. I doubt they ever really knew what they were trying to prove in this regard except that they were trying to prejudice the jury against his sexuality. It was bigoted, mean-spirited, unprofessional and ultimately counter-productive.

In my experience defending people, I have learned that heterosexual females are far less threatened than heterosexual males by such attacks. In the process of humanizing a male who is being portrayed as non-heterosexual, I have concluded that, generally speaking, females react to this charge with less immediate insecurity and judgment than heterosexual males. The females do not seem to have the same insecurities about their sexuality and seem more open-minded to different lifestyles. Of course, this does not apply to everyone.

One of my primary objectives was to humanize Michael Jackson. I planned to explain that he had never had a real childhood and did not trust adults. I wanted to explain that this wealthy, successful entertainer could have spent his millions of dollars in a profligate manner rather than devote his life to the cause of children. I presented him as a champion of children around the world because he is. I believed that mothers would relate to his lifestyle once I had explained it. I proved that he was a protector of children rather than their enemy.

We proved that Michael Jackson wanted to have an international holiday for children and that he had a rule that he would visit a children’s hospital before every concert. The jury saw videotapes of inner city children visiting Neverland and enjoying its zoo, amusement rides and theater. I am happy to say that our message, which was grounded in the truth, was well received. I think that the mothers on the jury liked him.

Again, intuition and instincts rule. They make the difference between bright lawyers who are “so-so” in court and those who excel.

B. The Racial Element

I would like to comment on my use of race in the Jackson case. I am known in Los Angeles to be quite vocal in my use of race in the courtroom, provided I believe it is appropriate. In the Jackson case, it became clear to me that I did not want to raise race as an issue. As I got to know Michael Jackson and the evidence, I realized that he is a unique personality who brings all races together rather than divides them. I believed this could be a great asset to us in the courthouse.

I was there to win, nothing else. The trial took place in a very conservative, blue-collar, primarily working-class community of mostly Caucasian people and, to a lesser extent, Latinos. Very few African-Americans or Asian-Americans reside in this venue. It was very unlikely that we would get any black jurors.

I asked Michael Jackson’s father to stop his television appearances where he was criticizing his son’s prosecution as racist. Whether or not he was correct was immaterial to me. I wanted to do what I thought would be effective in saving his son’s life.

During jury selection, a black female appeared on the initial panel. The prosecutor exercised a preemptory challenge and promptly removed her. I made a constitutional challenge at side-bar that was denied by the trial judge. To my surprise, a second African-American woman appeared on the panel. The prosecutors promptly removed her and I made the same fruitless constitutional objection at side-bar.

One of the intuitive challenges facing a trial lawyer is to determine what the other side is thinking. This begins as soon as you enter a case. During jury selection, I was always trying to fathom what the prosecution’s strategies were. Race was a major issue in this regard. How so?

As you all know, a trial lawyer has a certain number of preemptory challenges with which to remove jurors. No reason need be given unless your removal is challenged on constitutional grounds. Other jurors can be removed “for cause” if the judge determines they cannot be fair and impartial. There is no limitation on removing jurors for cause, but you need the judge’s approval to do so.

One exercises preemptory challenges with many factors in mind, including what you think the other side is trying to accomplish. In Jackson, the prosecution quickly began to “accept the panel,” meaning they were willing to utilize the jurors in the box as the trial jury. I believed they were doing this for strategic reasons. They thought that I would not accept the panel so early and they were, in effect, banking their challenges. They knew that a young African-American male was coming up through the ranks and could statistically make it to the final jury. In my opinion, they thought I was desperate to have a black juror and that I would do anything to see this happen. They hoped to bank their challenges and eventually “run a table” on me and remove many jurors that they probably did not care for.

This conclusion was strictly intuitive. I looked to the other side and saw three white male prosecutors and their white male jury consultant. The jury consultant was named Varinsky. He had been a consultant for the prosecution in three high-profile trials where convictions were obtained: Timothy McVeigh (who received the death penalty), Martha Stewart and Scott Peterson (who also received the death penalty). I watched these prosecutors and their consultant as they huddled and conversed. I believed they thought this case was indefensible and that my only hope was a hung jury. They believed I would do anything to obtain a single black juror to hang the case. I believed they were engaged in stereotypical, simplistic thinking about race and were willing to temporarily accept jurors while they banked their challenges for the future. They thought I would never accept any panel if there was any potential for an African-American juror.

I concluded they also believed that, even if I wanted to accept a panel before this black male appeared, the Jackson family would not permit it. Well, I shocked them when I accepted the panel with five preemptory challenges remaining. I saw their jaws drop. I believe the final jury had people they did not particularly want and that their strategy had backfired.

Consider one juror: He was a young, white disabled man in a wheelchair. His attitude and politics appeared very conservative; but remember, they were viciously attacking Michael Jackson’s make-up, skin and other things about his appearance. Who knows discrimination better than a young disabled person? Who is more likely to dislike these kinds of personal attacks than someone who is disabled?

During the trial, the prosecution schooled some of their witnesses to discuss Michael Jackson’s make-up and appearance. Michael Jackson suffers from a skin disease called vitiligo. This disease destroys skin pigment. One day Michael showed me his back by lifting his shirt. His skin is brown with white patches. He looks like a cow. He is very self-conscious of similar skin conditions on his face and this is why he applies make-up. You also see his security guards use an umbrella because his skin cannot accept sunlight.

I knew that the prosecutors were going to exploit his appearance. I also believed a young disabled man would take considerable dislike to this. It is difficult for me to believe that they wanted this kind of person on the jury. I think their gamble backfired in the way they attempted to bank their preemptory challenges.

This was a five-month trial. Not one juror was removed. Clearly these jurors wanted to remain on this panel and took their job very seriously. My instincts during jury selection were very important to our victory.

Conclusion

I hope I am not offending your dean and professors when I reveal some of my unconventional methods. As I said earlier, you must learn to understand and converse with the people who sit on juries. You cannot ignore the emotional content of any trial. Someone once advised me never to ask a question in a courtroom that I would not ask in a bar! Ordinary, hard-working people are not impressed with a sophisticated vocabulary. They want clear questions, and you want to come across as a decent human being.

Although we are taught to be perfectionists in law school, nobody is perfect in real life. All of us are fallible and make mistakes. Sometimes lawyers ask unartful questions and get embarrassed in front of juries when they have to withdraw them. They should not be embarrassed. This helps to let the jury know you are human. Arrogance and intellectual superiority are not admired by jurors.

Of course, some of our colleagues with all of their accolades and big firm prestige are not training themselves well for the courtroom. You cannot just hang out with self-satisfied, egotistical, pompous, arrogant, intellectually superior lawyers and learn the things I am describing.

How do you develop the instincts you need? One way is pro-bono work. Many years ago I began to do pro-bono work at a free legal clinic on Sunday mornings at a prominent African-American church in Los Angeles. I quickly realized that all of us were being helped: the people who needed assistance and the lawyers who donated their time. This includes law students who served as paralegals. Pro-bono work gets you in touch with ordinary people and their struggles. It gives you the insight and instincts we have been talking about. You gain, along with the people who receive your valued advice.

Following the Jackson verdict, I started my own free legal clinic at another church. Some local law schools in Los Angeles are giving course credit to students who donate their time as paralegals. When people who need help come to our clinics on Saturday mornings, the students take down basic information and describe what the problem is in our standard forms. They have the client’s sign basic documents and then sit with a lawyer and the client for a discussion.

Remember, you are not doing this for money. You are trying to understand what these people are experiencing and trying to make a difference in your community. It is also a way to pursue the ideals that many of you have in law school but tend to lose after you graduate. I get much more from these experiences than cocktail parties where lawyers tell each other how great they are! I am telling you the truth.

Taking your professional credential and going into poor communities makes you a better person and lawyer. It can only enrich your spirit and character and enhance your humanity. I cannot tell you how great it feels and how important it is to understanding your profession.

Only you can discover what combination of activities will give you a fulfilling legal career. In Los Angeles, we have developed a formula for free legal clinics, which we hope will be applied at every church. It is simple. We have the forms and invite lawyers to obtain them from us and learn the basic procedures involved. We invite law professors, judges and lawyers to come speak on subjects of concern to the community.

It may be landlord-tenant law, social security, criminal law, health care law or similar issues. We have had a mock small claims court trial at our clinic. The clinic exists in South Central Los Angeles, and I can assure you that lawyers who experience us often return. Many of them admit it is the most satisfying part of their professional life. The experience allows them to make a difference in a world set apart from partnership discussions, firm management and other general practice issues.

All of this works together if you care about people. You become a better person, a better lawyer and are a step closer to being the best attorney you can be in the courtroom.